Who Are We?

There are many people who contribute whatever time and expertise they have, and we couldn’t exist without the unsung public who contact us wanting to know what to do with all the boxes of tape they have. As with any organisation there is a core team, and they are as follows:

Founder & Researcher:

Dr Steve Arnold

Steve is a Broadcasting Historian and Digitisation Consultant, and worked as researcher on the BBC Genome project, mapping out the channels and sourcing the magazines for digitisation. He continues to be consulted and has digitised additional content and filled the gaps in schedule data where Radio Times wasn’t published. Steve is working closely with Radio Times as RadioCircle are handling the radio side of their Treasure Hunt campaign.

Media Specialist:

Richard Harrison

Richard is our media specialist and the one who found the missing Hancock, The Marriage Bureau, last year. When not transferring reels he is a teacher, writer, broadcaster and filmmaker with too much space in his house and feels the need to fill it with reels of tape! He has acquired numerous collections via auction, ebay, and donation, and systematically works his way through them all.

Restoration Expert:

Keith Wickham

Keith is an Actor, Voice-Over, and our restoration expert. He digitises material on an industrial scale and knocks shows into shape for re-broadcast. In some instances a single show can be made from a dozen or so off-air copies, so knowing a show exists isn’t the end of the story. Keith restored and reconstructed the start of the recently recovered Hancock and is the main contact within Radio Circle for Radio4Extra, so we can do what no other group does, and get the material rebroadcast and enjoyed by as many people as possible.

FAQ

Why are programmes lost?

The BBC - the majority of the recordings we have are BBC - didn’t keep everything it broadcast, and they were not alone, with the various ITV companies and ILR stations also being selective about what they retained. There are a number of reasons and it is worth understanding why before crying ‘cultural vandalism’.

For a large period, it wasn’t possible to suitably record programmes for use and re-use and programmes were transmitted live. Even when recording was possible, there wasn’t always the need – live broadcasting works and much is of the moment and will never be repeated. It was also costly. The BBC is a broadcaster, not a museum, so budgets were directed at new programming, with representative examples of programming kept for reference and re-use within new programming. The commercial stations existed to make money from broadcasting - once a shows financial potential had been exhausted it would be wiped so it didn't become a drain.

The cost of the media is one thing, but keeping everything on large, bulky reels of tape, or even when copies were pressed to vinyl, would require huge warehouses. There was a limited home market and the most popular shows like the Goons and Hancock were issued commercially, under licence, by well-known record labels.

Another factor is contracts. Performers, writers, musicians, and production staff all wanted to keep working. If there is a nice set of recordings on the shelf that can be continually trotted out, the work dries up. Unions and agents protected those they represented and contracts often stipulated an original transmission and one or two repeats. Why keep something if you can't re-use it?

Although it might not be politic to say, there were some real turkeys made. Why keep something that was an unresounding failure - better to bury or cremate the mistakes.

The bottom line is the BBC have a huge archive, but there are gaps that could be filled.

What are we looking for?

In short, anything that isn't held in an official archive like the BBC, the British Library or the BFI. We deal exclusively with audio/radio recordings but liasise with other organisations that specialise in film and TV to ensure nothing slips through the net and have often found soundtracks of television shows from a period before video recording was possible or affordable.

Recordings come in many shapes and sizes and most will be unfamiliar to those who have grown up in the digital age. There are various very early recording formats like wax cyclinder, but the earliest practical, but hugely expensive, method would be acetate disc. Blank discs could be bought and recordings cut into the surface. They are very fragile and rare, but when they do turn up they almost always have something of interest. Several Goon Shows have been recovered from privately cut discs - jazz enthusiasts appear to be the largest group to cut their own discs and Ray Ellington, Max Geldray, and the anarchic humour of the Goons struck a chord with them.

Open reel tape (1/4 inch) is, by far, the most common format for interesting finds as it's use spans from the 50s to the 80s, and comes in various sizes with recordings made at a number of fixed speeds. Initially the cost was substantial and tape was often reused, or recordings transferred to more econimical speeds to preserve tape (with a loss of quality). Last years discovery of the Hancock's Half Hour: The Marriage Bureau, was found on an early BASF tape.

Cassettes will be the most familiar of the older formats even if it just an image to represent 'retro' music. Far smaller and more accessible, but also considered far more disposable, this supplanted open reel for recording through the 70s and 80s and was the mainstay for those building up collections until digital formats were introduced. Many people transferred their open reel collections to cassette as the reels became more difficult to buy, and the cost of cassettes became cheaper. This means that although a cassette may not look that old (if 30 or 40 years can be considered not that old!) it may have recordings that are much older.

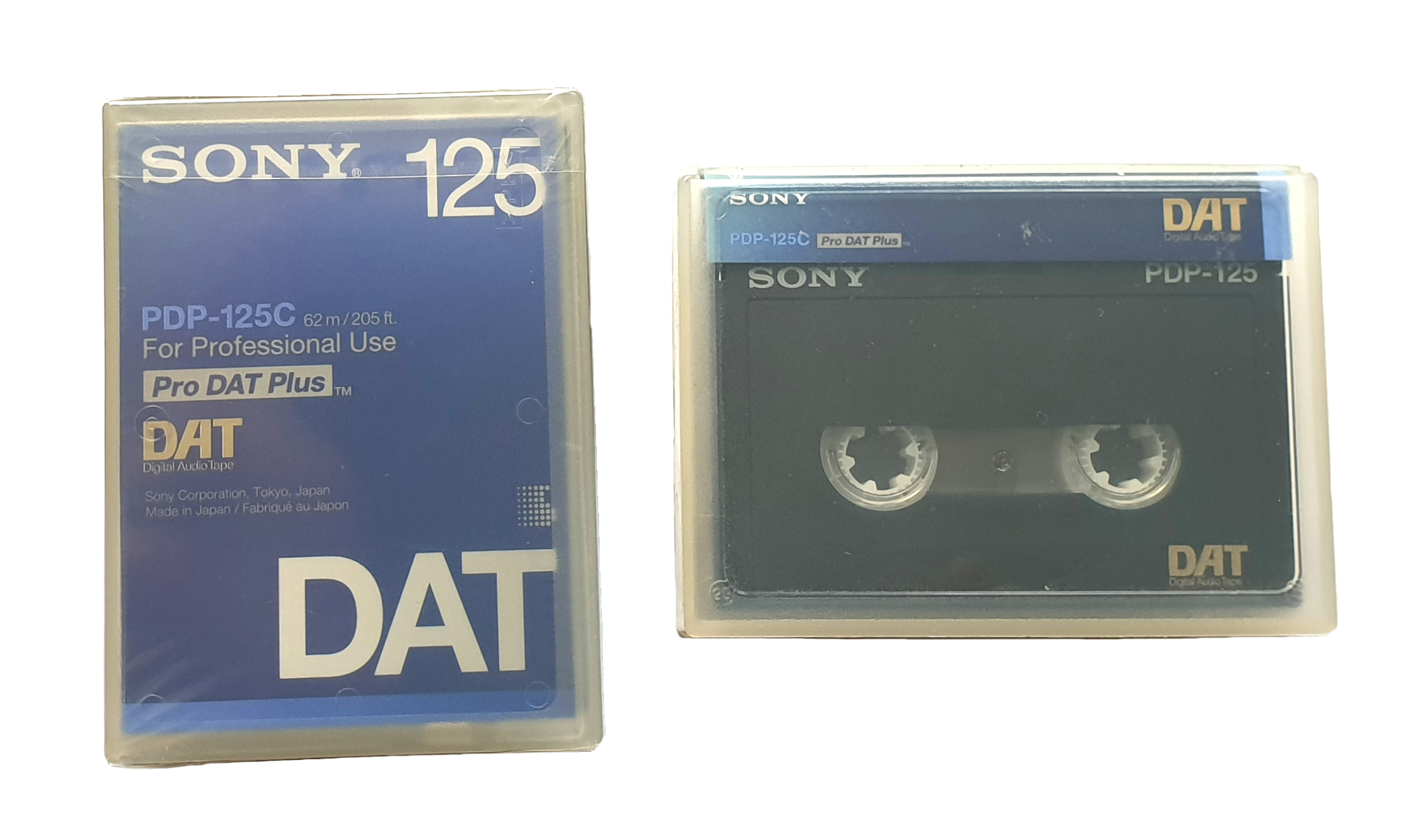

Digital media such as DAT, MiniDisc and recordable CD started to become viable for home recording in the 90s. While digital media is convenient to use and store, long-term survival isn't guaranteed, with some brands of CD (and later DVD) becoming unreadable realtively quickly. This applies to professional as well as home recordings, so some, rare, instances masters from the 90s can no longer be played.

Digital presents its own unique problem. People got used to the idea they could carry recordings about with them to listen to and wanted to carry more and more so they had choice. mp3 players were the answer - recordings were compressed in size by removing the sound that could not be heard on playback - this is known as lossy compression. Only where we have no other recording available will be keep hold of mp3s as reference - and we always try to trace the source of the mp3 to see if the original recording exists as restoration of shows is impossible on an mp3.

In addition to recordings we welcome the equipment they were recorded with as it all has a limited lifespan and we work through a lot of tapes! We also welcome magazines like Radio Times, TVTimes and London Calling as it helps us to research the shows. We also welcome ephemera such as tickets and flyers for recording sessions (guests can change last minute or are not detailed in listings magazines). We understand that some items have a financial or sentimental value, so we can arrange digitistion and return.

What do we do with recordings?

First of all we read any labels or catalogues that come with the recordings. This often gives us enough information to prioritise transfer, but reels and cassettes aren't always in their original box and, in most case, tapes and reels are unlabelled or just numbered - the corresponding catalogue lost.

We then inspect the physical recording to see if there are any issues. Recordings are physically cleaned where needed to protect the recording and equipment, and damaged spools etc. are replaced to avoid damage. In some, thankfully rare, cases reels of tape have deteriorated to a point where plastic backing tape has hydrolysed and becomes sticky. The only way to play these tapes is to bake them first and extreme care has to be taken as you generally only get one chance for playback.

Digital recordings are made and it is only then that we know for certain what is actually on the tape. Where we already have a copy of a programme, a comparison is made to ensure they are exactly the same and no improvements can be made. Some programmes we hold can be made up of a dozen off-air recordings as each has a problem - either an edited repeat, intereference during recording, an incomplete programme. We can't assume just because we have a show, we have the best or most complete copy available, so we look at everything.

Once digitised, recordings are held in multiple locations and in the cloud to secure their long-term future. Only in exceptional circumstances do we retain the original media.

Finally, we offer recovered material to the BBC (via Radio4Extra) for re-broadcast. We want as many people as possible to enjoy the recordings.

What don't we do?

We don't sell recordings, upload them to the web, or respond to requests for copies. We don't hold the copyright to any of the recordings so they are not within our gift.

What can you do?

If you have recordings that you believe will interest us, there are a few things that will make our lives easier. 1. Knowing what is on the tapes/cassettes. This can be Radio Times cuttings inserted in boxes, handwritten labels, or catalogues or lists and scans or photos will be fantastic. 2. Whatever you know about the collection. This might be 'I remember Grandad recording the radio as I was growing up' to 'I downloaded it from YouTube last week'. 3. Size. Number of tapes/reels and physical size so we have an idea for shipping. Again photos are ideal.

The more information you can provide initially, the less we will have to ask in subsequent emails or letters.

Any other business?

Always the catch all item on any agenda. We are not funded by any broadcaster or archive. All that we do at RadioCircle is done through a love of radio and at the expense of our members and we will always welcome any donations, however large or small, to help us in our quest.

Do we return anything sent to us? We prefer not to. Not only do we not have a budget to cover the cost of returns, we may not transfer the recordings immediately or in any fixed order - labelled recordings are usually done first as we know what to expect. Unlabelled recordings are left until we have a lot of spare time. Keeping track of what came from where is time-consuming and we would rather spend that time on saving recordings. What we normally do is provided the digital transfers electronically.

"I really must have my collection back". We know there are instances where collections need to be returned. Each of us has 'invested' time and energy into our hobby and we know how precious a collection can become. We discuss everything in full before we take delivery of any recordings so everyone knows what to expect.

Can I have a credit for the find? Certainly, RadioCircle will ALWAYS credit those who provide the recording in any annoucnements we make. We cannot, however, guarantee that other institutions, mainly the BBC, who take the recordings will do the same - we seldom get a credit ourselves!

Media

What follows is a quick guide to some of the recording media that we are on the look out for:

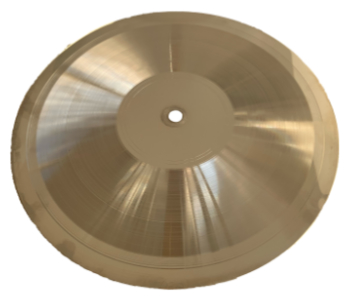

Metal master

These are rare, but turn up from time to time at auction and are generally a curio that a collector may have taken a fancy to. More likely to be framed and hung on a wall than bought to play.

Photo courtesy of Ian Beard.

14" TS Disc

The BBC Transcription Services took the best of the BBC output, pressed it to disc, and sold it to foreign radio stations all over the world. Most were commercial enterprises, so edits were made to show to allow for adverts to be inserted, and topical matter was removed.

There was a year zero cull of the catalogue in the mid 1950s, and only a small percentage was considered saleable and made it to the new catalogue. Anything pre 1955 is probably missing from the archives, and would most likely have been issued on whopping 14" diameter discs. By nature of their size, they were prone to breakages, and programmes usually spanned two or three discs, meaning that what turns up is usually just a third or half of a complete show.

Photo courtesy of Ian Beard.

BBC Reels

Every now and then a professionally recorded reel turns up. These were used by internal departments, sent to journalists, or dumped in skips when the show was complete (and fished out by various people who were curious). Sometimes the contents are already in the archives but more often not. If nothing else, the labels can provide information about recording and transmission dates and possibly even details of who worked on a show.

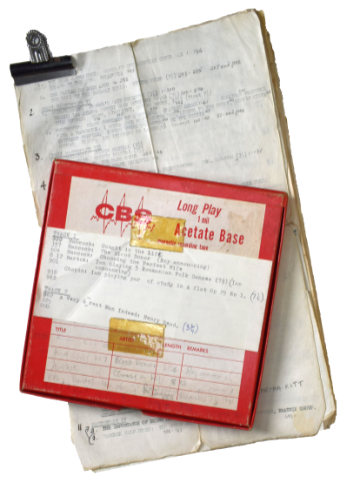

Labelled reel and catalogue

Sometimes we are lucky and collections are neatly labelled, there may be a catalogue to go with them, and all the reels are in the boxes they should be. This makes life a lot easier in sorting out the priority for transferring, but we will always check all reels just to be sure that the contents are what they say they are. If luck is really on our side the tape will have been started early and catch the end of the previous show and in rare instances the tape may have been left running getting the following show as well.

CD, MiniDisc and cassette

Familiar media from the last few decades. The ubiquitous casette that can yield anything, irrespective of the vintage of the cassette itself and are often the last gasp of shows originally recorded on open reel and transferred to cassette to downsize. The recordable CD, usually containing copies of programmes that were recorded on other media first, and the MiniDisc a useful format for recording and editing radio programmes that came along too late to make a major impact.

Other sites of interest

British Comedy and Drama

Established in 1996 and initially concentrating solely on radio comedy, the site has expanded to include television with drama in a section of its own. It is run by a long-standing member of the radio circle.

This site is no longer updated, but the original research has been left in place for others to refer to (or to pass off as their own work in Wikipedia!)

BBC Programme Index (Genome)

Around 2010, the BBC undertook the mammoth task to digitise the London edition of the Radio Times, starting in 1923 and running through to 2009, when the BBC website had established its own archive of schedules. A compelte set of magazines was a scanned and Optical Character Recognition employed to extract the listings text. The resultant database can be searched and has speeded up research work.

- © RadioCircle 2022. All rights reserved.

- Original template: HTML5 UP